The real Oscar buzz began for Hattie McDaniel, who played Mammy in Gone With the Wind, after she nailed a scene where she tearfully relays to family friend Melanie (Olivia de Havilland) that Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) is suicidal over the death of his baby girl.

While black folks and black newspapers alike didn’t “give a damn” about Gone With the Wind (GWTW)—the film adaptation of a racist novel that glorified slavery—they were excited that McDaniel could potentially make history with a Best Supporting Academy Award win.

The actress couldn’t rely on buzz, however. Nor would she could depend on Hollywood to do the right thing. Instead, she walked into producer David O. Selznick’s office in Culver City, Calif., with a stack of articles that and gently leaned on him to submit her name for Oscar contention.

Black journalists urged readers to write Selznick and demand that McDaniel be put in the running, and a letter from McDaniel’s sorority, Sigma Gamma Rho, predicted that discrimination and prejudice could be wiped away if she were to win. Selznick agreed with her supporters that her performance was Oscar worthy, and put her name forward. (Awkwardly enough, one of the actresses she was up against was co-star de Havilland).

McDaniel’s journey to that moment was a slow, arduous climb. Though she’d come from a talented family of entertainers in Denver, only her two older brothers had consistent success in show business. The eldest had died in his 30’s, while Sam McDaniel, a few years older than Hattie, landed bit parts and played Deacon McDaniel on CBS’ radio show, the Optimistic Do-Nut Hour. Mostly he earned his living as a bandleader.

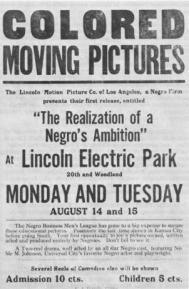

Baby sister Hattie struggled, often taking domestic work, as her mothers and sisters before her. Though she performed often, and even toured with a 1929 Show Boat production, the Depression gutted her entertainment career, and she came west from Milwaukee where she was squeaking by in 1931. In Los Angeles, she was a recurring cast member on Sam’s radio show and gigged with the Sarah Butler’s Old Time Southern Singers. She also took on domestic work to make ends meet, just as older sister, Etta, did. All three siblings got roles in moving pictures here and there.

With the success of 1934’s Imitation of Life, featuring a white woman and a black woman as friends (actresses Claudette Colbert and Louise Beavers), bigger, brown-skinned women such as Beavers—and McDaniel—were suddenly in vogue. And when McDaniel got word that Selznick was casting GWTW, she read the 1935 Pulitzer Prize winning novel several times, determined to claim the part of Mammy for herself.

Landing a contract would mean guaranteed pay for several months, but it required patience as Selznick milked the free publicity by dragging out the audition process. He even sent talent scouts to acting troupes around the country. Several stars, including McDaniel, screen tested for their parts more than once.

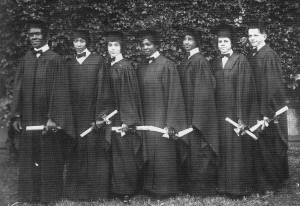

Once she’d won the role, shot her part, and been nominated for the Oscar, McDaniel became the first African-American to attend the ceremony, then-12 years old. In the background, actor Clarence Muse, columnist and actor Harry Levette, and journalist Earl Morris were the among the first African-American Academy voters to cast ballots that year, according to one of Hattie’s biographers, Jill Watts.

Still, some black folks were not appeased by what they perceived to be window dressing on a shack of a story that demeaned blacks and made slavery seem tepid compared to the real thing. Walter Francis White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People nudged Selznick for several years to consult with him (or a black scholar) to expand and enhance GWTW’s black story line. Selznick corresponded with White, and yet held him at bay. But the producer could not stop protesters from picketing his feature outside theaters around the country, or at the Oscar ceremony itself at L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel.

That pivotal night, Fay Bainter, the previous year’s Best Supporting winner took the stage and proclaimed how happy she was to present this “particular” honor which “enables us…to reward those who have given their best regardless of creed, race or color…” With that, she teed up the announcement that McDaniel had scored the momentous victory and an historic first.

McDaniel bounded up the steps to accept her award—back then a small

plaque with a petite Oscar figurine welded to it—and forgot(?) the speech Selznick International had prepared for her. Instead she spoke from her heart.—and very possibly from a speech that she and journalist and friend, Ruby Berkley Goodwin Ruby Berkley Goodwin, had written together. (GWTW went on to take 10 Academy Awards, including best picture.)

Flowers and congratulatory telegrams poured in from around the country, with papers, big and small, championing the victory. But within a year or two, McDaniel was again desperate for work. Her career floundered until 1947, when she landed the role of Beulah on the radio.